[ad_1]

Ahoy! Back after a restful summer and now drinking from the MEV firehose. There’s so much happening; it reminds me of DeFi in the fall of 2019. Look out for another MEV piece next month.

– Chris

A lot has changed in the three years since Flashbots released MEV-Geth in its attempt to “frontrun the MEV crisis”. Ethereum has been through a market boom and bust, and successfully shifted to Proof of Stake – a major technological feat. All the while, the battle for the value that leaks from economic transfers on blockchains has grown more intense. Attempts to eliminate MEV have failed; the reality is that block proposers will always have an incentive to take advantage of their privileged position.

The allure of MEV profits now threatens to engulf Ethereum’s sovereignty and censorship-resistance. A central overarching concern remains: that the hunt for MEV will centralize stake in Ethereum. If only the most sophisticated actors running validators are able to reap the rewards of MEV, then ETH holders will gravitate towards these validators. This is because they can offer higher yields with MEV rewards on top of the protocol-enforced yield.

This centralized future has, at least for now, been avoided through MEV-Boost, which gives large staking pools and solo validators equal access to the fruits of MEV extraction. Yet MEV-Boost was always intended as a stop-gap solution. And while it has generated a robust MEV ecosystem of professionalized players, the industry is becoming increasingly centralized and relies on trusted parties and a single software client.

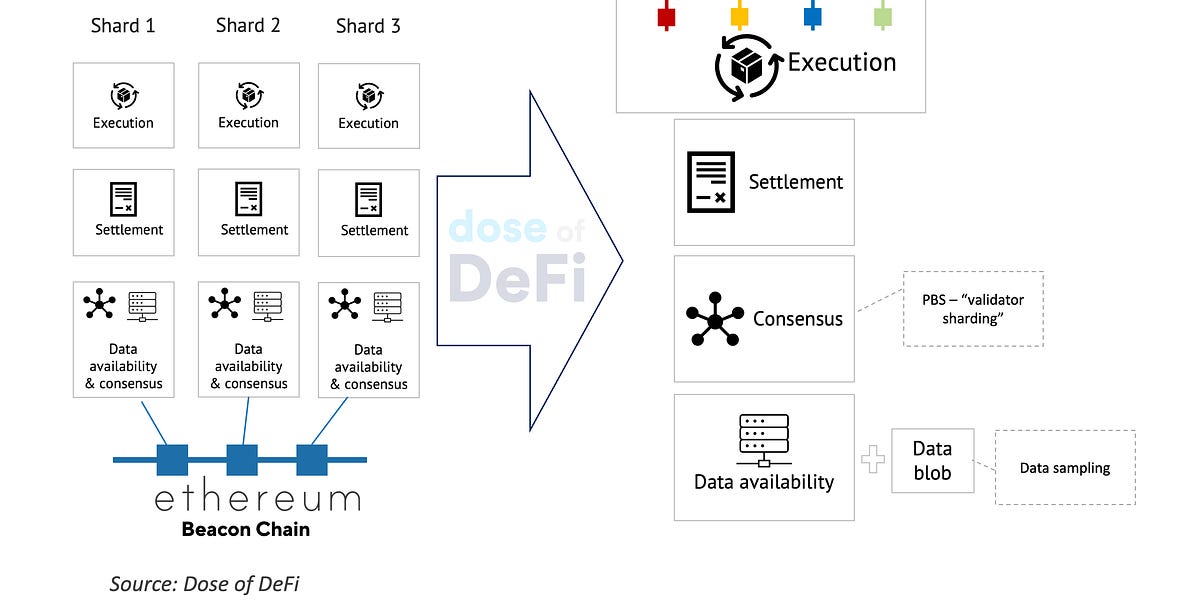

We argued last December that “the optimal solution to the MEV crisis will be a standalone, decentralized network focused entirely on sequencing transactions.” However, this is still a (slow) work in progress. Changes to the core Ethereum protocol to enshrine Proposal Builder Separation (PBS) are needed, yet that will not be enough.

We remain confident that the solution to the MEV crisis lies outside of Ethereum, but are now convinced that it will not be a single monolithic solution for addressing all MEV leakage. Instead, different decentralized but vertically-integrated MEV supply chains will emerge that specialize in extracting MEV for specific applications. We also contend there is too much focus on MEV from CEX-DEX arbitrage, which currently accounts for ~60-70% of MEV volume and profits. If DeFi emerges as the foundational global financial market, this won’t be the biggest MEV problem faced.

PBS is the overarching design philosophy that ensures that Ethereum remains decentralized and neutral. It’s a widely accepted precondition to any MEV resolution. Ethereum currently achieves PBS through MEV-Boost, the Flashbots-provided software run by validators that allows a randomly selected block proposer to auction off the right to build the most profitable block to the highest bidder. So far, PBS has democratized MEV rewards by allowing solo stakers to partake without employing sophisticated MEV strategies of their own. Yet the rest of the MEV supply chain remains fraught with centralization and censorship concerns.

As a refresher, the diagram illustrates the major components of the MEV supply chain, a term first coined by Stephane Gosselin, founder of Frontier Tech and formerly of Flashbots.

The Ethereum protocol’s architecture is intended to be much simpler. The design naively assumes that for every block, a randomly selected validator will locally build a block sifting through the public mempool for transactions submitted by users with the highest gas fee.

The three additional players in the MEV supply chain – searcher, builder, and relayer – coordinate with validators through MEV-Boost, which is currently run by 93% of Ethereum validators. Of the three, the builder is the most prone to centralization, while the relayer is the least rewarded. Searchers used to be the prototypical shadowy super-coders, but now they’re teams of developers: some truly anonymous while others are major trading shops. The economic relationships between searchers, builders, and relayers is shrouded in mystery. Payment for flow is common, but since these relationships are off-chain, they’re not observable.

Increasingly, there are structural advantages for vertically-integrated builders. Just this week, one of the major block builders, Blocknative, announced that it would stop serving as a trusted relayer. It cited the costs of running a relayer (reportedly $500k a year) without any associated revenue. This could have made economic sense if Blocknative had its own team of searchers, but as a US-based company, it’s understandably straying away from any activity that could draw the ire of regulators.

Bloxroute, also a major builder, has not turned their relayers off, but it’s also hedging its regulatory bets. It runs two relayers, one dubbed “regulated”, which censors blocks with OFAC-sanctioned addresses, and the other “max profit”, which….doesn’t. With the exit of Blocknative, there are now only four major relayers: Bloxroute, Flashbots, Ultrasound (headed by Ethereum researcher Justin Drake), and Agnostic (from the Gnosis team).

Now that we’re up to speed on the current supply chain and its challenges, let’s flip back to the mechanics of MEV extraction – and why it’s causing such a ruckus. To many, MEV is just frontrunning trades, or worse, sandwiching them (trading the transaction before and after a transaction in the mempool to lock in profits). This is unequivocally bad for regular users. In its most productive form, MEV is on-chain arbitrage between different DEXs. A trade goes through a Uni v2 pool pushing a token price up or down, and mighty MEV bots compete to rebalance other liquidity pools and incorporate the new token price. These are the easiest MEV examples to understand, but they are not the most common.

In fact, the majority of MEV extraction is CEX-DEX arbitrage. This MEV hurts DeFi liquidity providers, not traders. The deepest market for ETH is not on Ethereum: it’s on Binance. And when the price of ETH changes on Binance, there’s a mad rush to trade against Uniswap LPs, who have not yet incorporated the new price. The winning MEV must be the first transaction in the new block after the price change, which is referred to as being “top of block”.

After a significant price change on Binance, an MEV bot must bribe – ahem, pay – the lucky validator who is randomly selected to propose the next block. Of course, in the world of PBS and MEV-Boost, the MEV bot sends its transactions first to a block builder to fill with other transactions, who then pays the lucky validator (as long as they propose the suggested block). All of this happens within 12 seconds (the time in between blocks on Ethereum). Max Resnick of Special Mechanism Group (SMG) explained the CEX-DEX arbitrage in detail at Flashbots MEV Salon in Paris as well as in the full technical paper.

The troubling conclusion: when there is volatility on Binance (a 1% or more change in price), the most sophisticated builders always win the bid for the next block because they’re willing to pay more to be in the lucrative top-of-block position. This creates a circuitous cycle. Sophisticated builders pay more when there is an MEV opportunity in the top of block, meaning they win more of these juicy blocks. This makes them more likely to get private order flow from searchers, and with more private order flow, they can bid more to get their block included. Or, as Max from SMG puts it, “Winners have incentives to get better at winning”.

This is a latency war with little societal benefit. Yet unfortunately, it’s damn near impossible to prevent. The early bird catches the worm; the most sophisticated players will always get there first. There is considerable research going into solving this problem, and the current consensus solution is to allow for auctions of partial blocks.

We think these research efforts are noble but misguided. DeFi’s end game is not to play second fiddle to TradFi. It’s hard to imagine now, but the whole point is that price discovery should not occur on a centralized exchange.

Of course, there will always be market-moving information from the off-chain world, where being the first to trade on-chain comes with some advantage. The most obvious example is the Fed announcing interest rate changes. It will never be on-chain first. Looking ahead, MEV in the future will not look like MEV that is extracted now. MEV “solutions” should be generalisable and not tailored to the current problems of the day. Afterall, if Ethereum succeeds, won’t Ethereum be where price discovery for ETH is?

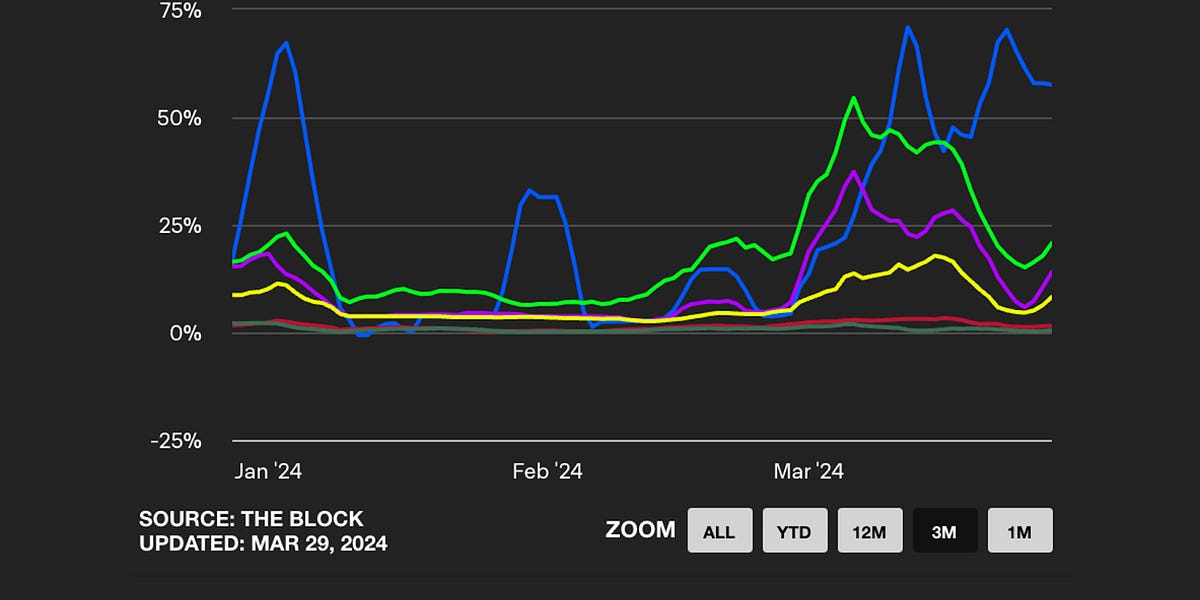

It’s incredibly hard to see the whole picture when it comes to MEV – it’s a dark forest! Still, when it comes to data, EigenPhi has some of the best MEV visualizations. The chart below shows which actors in the supply chain are earning the most profits (relayers would be $0).

Most interestingly, EigenPhi identified that a significant portion of the MEV rewards for validators occur outside of MEV-Boost, meaning that some validators are already developing their own MEV supply chain separate from MEV-Boost. It would be fine if these were solo stakers, but the more likely scenario is that large staking pools are beginning to run their own internal MEV strategies. If true, this could set-off an upward spiral, where higher profits produce better yield, which attracts more and more stake, allowing the staking pool to pay more for private order flow.

Much like how MEV can be extracted from transactions sent to the public mempool, MEV opportunities could also be sniped by entities within the MEV supply chain. A searcher who discovers an MEV opportunity sends it to a builder in return for a share of the profit. The builder then packs the juicy bundle into an entire block and pays the winning validator to propose the block. In the current design, nothing stops the validator from simply copying the searcher’s transaction submission and replacing it with its own, cutting out the searcher and builder. The reputation of the relayer is what prevents this alpha sniping.

There is no crypto-economic guarantee because PBS is achieved outside of the protocol through MEV-Boost. There has been considerable research on how to enshrine PBS (ePBS) into the Ethereum protocol so there would be no need to trust a third-party relayer to facilitate the builder payment to the block proposer. This is technically challenging and would require changes to the Ethereum protocol (but likely not consensus). PEPC (Protocol-Enforced Proposer Commitments), developed by Barnabe of the Ethereum Foundation, is the most developed example, but we’re still at least 18 months away from possible implementation.

This design does remove the need for a relayer – by creating a neutral way for builders and block proposers to transact – but it will not create an economically-viable competitor to a trusted relay. As Mike Neuder explains in an ETH Research forum post, relayers would still be superior for high-value blocks, like CEX-DEX arbitrage, while also allowing cancellation support.

The one thing that ePBS would improve is censorship resistance. Many of the designs feature the use of an inclusion list of transactions that must be part of the next block. So even if the largest builders were all heavily regulated entities, they couldn’t collude to exclude OFAC sanctioned addresses, for instance.

There’s no shortage of solution ideas when it comes to the MEV crisis. Yet too often, they’re presented as a silver bullet that fixes all problems at once (ahem, fair ordering). We believe that any resolution to MEV extraction must start at the app design phase. Most good app developers are already trying to minimize MEV, but they should realize that there will always be some value leakage. MEV cannot be eliminated. Instead, they should be proactive about engaging directly with MEV supply chain players. Payment for order flow is not an inherently bad thing – only when it’s hidden.

Next month, we will look at the parties taking the lead in MEV supply chain engagement, including Uniswap, Cowswap, SUAVE and Bloxroute & Ambient’s smart routing.

-

Coinbase goes to Washington Link

-

Friend.Tech Analysis (MEV, volume, revenue, impact on BASE) Link

-

Overview of the RWA asset landscape Link

-

Connext launches airdrop and new constitution for DAO governance Link

That’s it! Feedback appreciated. Just hit reply. Written in Nashville, which is in the first week of a new mayor! So interested in MEV these days.

Dose of DeFi is written by Chris Powers, with help from Denis Suslov and Financial Content Lab. All content is for informational purposes and is not intended as investment advice.

[ad_2]

Source link